Tribolium castaneum – the red flour beetle

The Tribolium beetle work is based at UEA where we have established a number of replicate lines that are being tested for the consequences of sexual selection, inbreeding and thermal stress.

Thermal sensitivity of male fertility

Our climate could warm by 5°C by the end of the century. A warmer atmosphere should be more hazardous and heatwaves more extreme and frequent. Hundreds of species have shown stress responses to warming for years. For example, species ranges on have shifted 17 km towards the poles every decade. However, if the stress is too great extinctions occur; currently we have limited understanding why.

We are looking at one potential cause; the impact of heatwaves on reproduction. In warm-blooded animals heat stress reduces male fertility. However, cold-blooded animals have hardly been looked at despite being way more abundant and potentially more vulnerable. The red flour beetle has several advantages to study the impact of heatwaves on reproduction.

Initial work has found that 5-day heatwave simulations (5 to 7 °C above the beetles preferred temperature) damaged male, but not female, reproduction. The damage was due to heatwaves reducing sperm production, sperm viability, and sperm migration through the female. Inseminated sperm in female storage was also damaged by heatwaves. Trans-generational impacts from heatwaves were discovered, sons produced from heated sperm subsequently produced fewer offspring and died earlier.

Initial work has found that 5-day heatwave simulations (5 to 7 °C above the beetles preferred temperature) damaged male, but not female, reproduction. The damage was due to heatwaves reducing sperm production, sperm viability, and sperm migration through the female. Inseminated sperm in female storage was also damaged by heatwaves. Trans-generational impacts from heatwaves were discovered, sons produced from heated sperm subsequently produced fewer offspring and died earlier.

See here for the 2018 nature communications paper, here for a video summarising of our findings, and here for a list of media coverage.

There are many outstanding questions we are working on including:

- How heatwaves are affected by an individual’s life stage and previous exposure history?

- Whether males can recover from heatwaves?

- If populations can adapt to increasing temperatures and if adaptation helps male reproduction cope with extremes?

Experimental evolution of sexual selection

Sexual selection was Darwin’s second great idea, explaining the evolution of a fascinating array of sights, sounds and smells that help in the struggle to reproduce – sometimes at the expense of survival.

What have we found?

Godwin et al. (2017). Experimental evolution reveals that sperm competition selects for longer, more costly sperm. Evolution Letters, 1, 102-113.

Theory predicts males should invest in high sperm numbers to win post-copulatory competition against rivals but what if there are other ways to win at sperm competition?

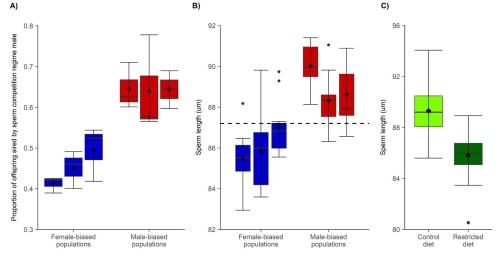

Males from experimentally evolved male-biased regimes gain a significantly greater share of paternity when in competition with a rival (Figure A), and have significantly longer sperm (Figure B). Males on a restricted diet produce significantly shorter sperm (Figure C), demonstrating the cost of sperm production.

Read more on the UEA CEEC blog: Sperm Size Matters

Lumley et al. (2015). Sexual selection protects against extinction.

Nature 522, 470–473.

Almost all multicellular species reproduce using sex, but its existence isn’t easy to explain because sex carries big burdens, the most obvious of which is that only half of your offspring – daughters – will actually produce offspring. Why should any species waste all that effort on sons?

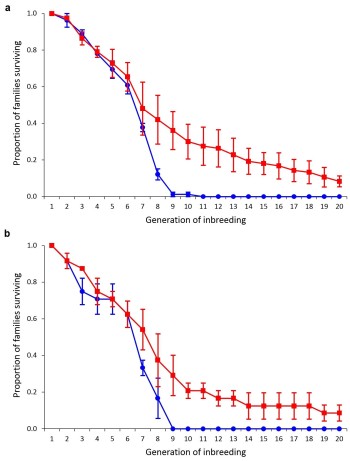

Our research shows that competition among males for reproduction provides a really important benefit, because it improves the genetic health of populations. Sexual selection achieves this by acting as a filter to remove harmful genetic mutations, helping populations to flourish and avoid extinction in the long-term.

![]()

For a short overview of this work see this article from

The Conversation, ‘Why men are not biologically useless after all…’.

Michalcyzk et al. (2010). Experimental evolution exposes female and male responses to sexual selection and conflict in Tribolium castaneum. Evolution 65,

Evolution of polyandry

Michalcyzk et al. (2011). Inbreeding promotes female promiscuity. Science

Why do so many females of so many species mate with multiple males, when we know that there are costs to females of polyandry, and that a single male can usually provide a female with full fertility?

Using inbred populations we compared individual female reproductive success (= the number of surviving offspring produced) in these with outbred controls, depending on whether they mated with one or five different males.

We found was that there were no benefits to females of promiscuity in normal, outbred populations. However, within inbred populations, females that mated with 5 different males had about 50% higher reproductive success than females who mated with just one male. Because inbred and outbred males have identical fertility, the result tells us that females in inbred populations used promiscuity to either avoid fertilisation by genetically incompatible sperm, or promote fertilisation by more compatible sperm.